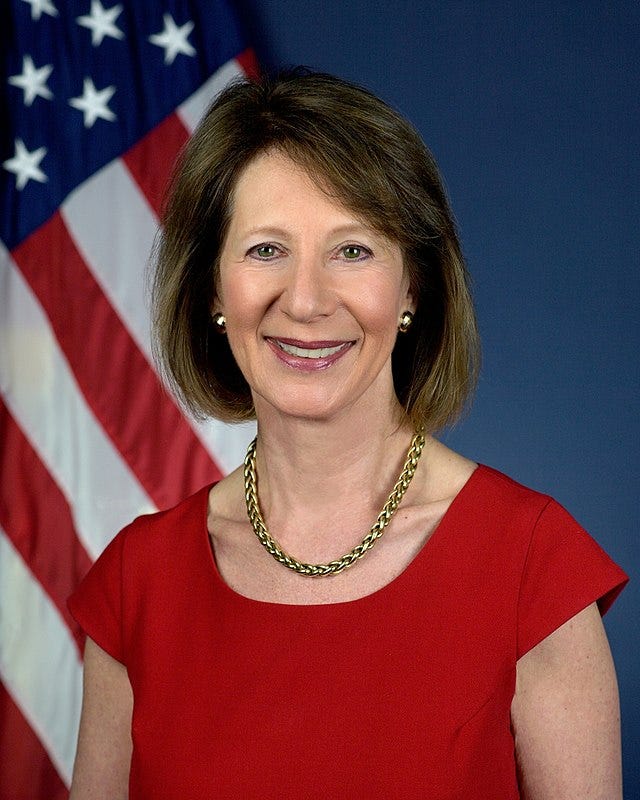

Diana Furchtgott-Roth (Heritage Fellow and GWU Adjunct Professor) joins the podcast to discuss her career including her government service in the Reagan, George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush and Trump administrations, along with her current work on environmental regulation and infrastructure.

Jon: “This is the Capitalism and Freedom of 21st Century Podcast, where we talk about economics, markets, and public policy. I'm Jon Harley, your host. Today I’m joined by Diana Furchtgott-Roth, she’s an economist, Director of the Center for Energy, Climate and Environment at the Heritage Foundation, which just celebrated its 50th anniversary, and is an adjunct professor of economics at George Washington University. Diana also has extensive experience in Washington, D.C., and has worked across four different presidential administrations in various senior economic policy positions. She worked at the Reagan Council of Economic Advisors, the George H.W. Bush Domestic Policy Council and the Office of Policy Planning. She worked at the George W. Bush Council of Economic Advisors as Chief of Staff and Labor Department Chief Economist, and in the Trump administration, she worked as the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology at the Department of Transportation and as the Acting Assistant Secretary for Economic Policy at the U.S. Department of Treasury. She's also married with six children and has had an unbelievably successful career. Welcome, Diana.”

Diana: “Great to be with you, Jon. Thanks so much for having me on today.”

Jon: “Diana, I want to just start off with where you grew up and how you got interested in economics.”

Diana: “Well, I grew up in England, and my father was an economist, so we talked about economics over dinner, and I think everyone in my family is interested in economics, and that's certainly where I got my first introduction to economics.”

Jon: “In what era, what was going on in the U.K. at this time at the national level? Was there anything happening that was particularly interesting to you or that was particularly formative?”

Diana: “Well, this was the 1960s going to the 1970s. There was a lot of industrial problems with coal strikes and the entire socialization of the economy that then Margaret Thatcher would then disrupt in the late 1970s, early 1980s. So, it was a very interesting time. Whether government was indeed a solution to the problems that Britain had at the time or whether more private sector activity and involvement would be a better solution. So, we had a lot of discussions about that.”

Jon: “Right. In my understanding from the 1970s U.K., there was a lot of tumult. There was, I think, some issues with the U.K. debt, but there were a lot of challenges at that time. The Thatcher era was often viewed as sort of a correction to that tumultuous time. I want to dig into your experience in government because I think there's just so many interesting things that I think our listeners can learn from your career and your incredible government service. And I want to start with your time at the Reagan Council of Economic Advisors. You know, the 1980s was certainly a really interesting time in economic history. The Reagan Council of Economic Advisors employed many famous economists, including yourself. It employed folks like Martin Feldstein, Larry Summers, Paul Krugman, and John Cochrane. I think many folks may not be aware of this, how many incredible economists today, who we all know, were there at one point in the 1980s. You were there when the Tax Reform Act of 1986 was passed. It cut the corporate tax rates from 70% to 35%. It cut personal tax rates below 30%, and was really the cornerstone to the Reagan tax reform, and one of the most consequential pieces of tax legislation in the past 50 years. How did that come together, and what was it like?”

Diana: “Well, it's really funny that you ask, Jon, because usually staff at the Council of Economic Advisors are hired on an academic year basis. There's a rotating group of academics that go through, but in May I got a call saying someone had unexpectedly left, and I was working on taxation and revenue estimates for a small company called the Fed Economics, and they wanted someone who had experience in taxation to go over to CEA, so they said, would you come? Well, first I said no, because it would have been a pay cut, and then a week later I called back, and I said yes, I would. And it was the most important decision I made career-wise. It was such an exciting place to be. And you get a high every time you walk into the old executive office building with its beautiful marble floors and its pillars. And we were working on different tax bills. There were a lot of tax bills that were going through Congress at the time. And in Washington, if you bet that something is not going to pass, you're generally right. So, at the time in May, I didn't know that the Tax Reform Act of 1986 was going to pass. All I knew is we were working on different tax bills and looking at different revenue estimates, talking to people about what a tax bill should look like. And then it turned out that the Tax Reform Act of 1986 was signed into law. And here, what we had been working on suddenly materialized. So that was very exciting, very exciting indeed. The Reagan administration was overall a wonderful place to work because you could talk about anything. There weren't these communications people in the policy meetings. As long as it had to do with cutting taxes and cutting spending, you could talk about it. So, the CEA, the Council of Economic Advisers, could have meetings on privatizing the post office, on selling the national parks, on charging for the national parks, all these things that would be, in a different administration, perhaps politically very incorrect. But as long as it was about cutting taxes and cutting spending, we were allowed to talk about it. It was a very exciting environment.”

Jon: “That's fascinating. And what an amazing time to be serving in government. I want to flash forward to the Georgia HW. Bush administration reserved on the Domestic Policy Council and the Office of Policy Planning. Could you explain what the Domestic Policy Council does and what its function is, along with the Office of Policy Planning? These are two increasingly important departments within both the White House Executive Office, but I think a lot of people may not be quite as aware.”

Diana: “First, I was the Deputy Executive Secretary of the Domestic Policy Council. My boss, Richard Porter, as opposed to Roger Porter, there was Roger Porter and Richard Porter. He said that they were looking for new ideas in domestic policy because President H.W. Bush was accused of not having enough domestic policy ideas. So, our job was to get together a group of policy ideas that would be in preparation for the campaign and that would do well with voters. So, we had some really interesting ideas, some of which went somewhere and some of which didn't. One idea that didn't go anywhere was cutting capital gains taxes by redefining capital gains as capital gains after inflation. So quite a lot of capital gains is inflation. You have these inflationary gains. So, we thought that if you redefined it as capital gains exclusive of inflation, that would immediately lower capital gains taxes. Because, of course, at that time, one could not get a capital gains tax cut through Congress. That idea, unfortunately, was one that did not go anywhere because the White House said that this was too adventurous. They didn't think that they would be able to support it in legal law and you couldn't just redefine capital gains. But that was a great idea, and I highly recommend it to any future administration.”

Jon: “Right. Even in 2023, capital gains tax brackets are not indexed to inflation.”

Diana: “Yeah, they're not indexed to inflation.”

Diana: “That's actually why capital gains have a lower tax rate. It has a lower tax rate because it includes inflationary gains. But it's not indexed to inflation. So, what would be better would be to make it more precise and index it to inflation, which perhaps when it was first put in place would be difficult to do. But now with computer programs, it's very easy to do. It's very easy to do it now.”

Jon: “Right. But the 1986 tax act, the Reagan Act, that did index ordinary income, so individual income, labor income tax brackets to inflation. At the time, inflation was very high in the 1980s, and there was this issue of bracket creep, and inflation would push people into higher tax brackets effectively when you're adjusting for inflation. That still is not the case on capital gains even. Even over 30 years later.

Dina: Yes, exactly. Yes, yes and you find that when people, for example, bought a house when they were just starting out and then they sold it when they retired, there was a huge run-up in home prices during the end of the 20th century. A lot of this would be inflationary gains. They were paying taxes on inflationary gains. They don't benefit from the gains.”

Jon: “Right. And so, we have this Office of Policy Planning and Domestic, which I believe was at some point renamed the Domestic Policy Council, if I'm correct. And then the Bill Clinton administration in the 90s also created the NEC, the National Economic Council as well, within the executive office. And that, I think, has become increasingly one of the sorts of more powerful arms of economic policy planning within the White House. And part of this is, I think, coordinating economic policy with Congress and sort of organizing priorities. Another part of this is working on executive orders. When you were in the George H. W. Bush administration working in the Office of Policy Planning and the Domestic Policy Council, I think George H. W. Bush signed an executive order allowing private sector investment for federally funded infrastructure investments. Could you talk a little bit more about that? It seems like today, obviously, it seems like an obvious thing, but it's a smart thing to allow private companies to help to work on things like airports and things like that. But this wasn't the case prior to the late 1980s, early 1990s?”

Diana: “No. In 1992, if a piece of infrastructure had federal funding, then it couldn't have private sector investment. This was especially a problem for airports, because municipality cities didn't have enough funds to maintain the airports, and air traffic was increasing. So, we drafted an executive order, which George H.W. Bush later signed, allowing private sector investment in those pieces of infrastructure that had received federal funding. And this became tremendously important, because it allowed more funds, more private sector funds, to flow into certain projects. And President George, President H.W. Bush, he was very enthusiastic about this, and he saw this as a way of increasing investment in certain infrastructure projects. After I left, under President Clinton, the National Economic Council and the Domestic Policy Council were vastly expanded. They were set up as more coordination councils, and they coordinated the work in the different cabinet agencies. When I was there, the Domestic Policy Council was a small group, headed by Richard Porter. It just had about three or four people in it. The National Economic Council was headed by French Hill, who is now a congressman from Arkansas. And he and I both worked together. He was in the NEC then, in the George H.W. Bush administration, and I was in the Domestic Policy Council.”

Jon: “Wow. It's fascinating history, and to think about how these economic policymaking bodies have evolved over time, also along with the Council of Economic Advisers, which was started in the 1940s with the Employment Act and how that has evolved over time as well. And, of course, much economic policy is also decided from Treasury as well, increasingly so, I think, in the current era. So, I want to jump and flash forward to the George W. Bush administration, so Bush 43, and what it was like working at the Council of Economic Advisers then. In the early 2000s, you were there when the Bush tax cuts were being passed, also this was in the post-911 era, there was a recession following the tech boom and burst. What was it like at that time? What was it like pushing the Bush tax cut program, certainly amid an administration that had come in on very strong domestic policy ideas, compassionate conservatism. We think about Social Security reform. We think about education reform. We think about tax cuts. That was a huge part of the Bush 2000 campaign platform. Of course, 9-11 was an event that really changed the course of the George W. Bush administration with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that would follow that. But I'm curious, what was it like working on the Bush tax cuts in the early 2000s at CEA?”

Diana: “Well, President Bush came in with a mandate to lower taxes, and the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 was passed in May. That helped lower tax rates and remedy a number of inequities in the tax code, which thereby encouraged more investment. There was a big push to complete this tax bill, and it was signed into law in May before one of the Senators actually switched parties and threw the Senate to, as I recall...”

Jon: “Jim Jeffords, I think.”

Diana: “Exactly, that was Jim Jeffords. Yes, exactly. It took a lot of negotiation on the President's part. Then after that, we switched the focus to Social Security. President Bush was a big advocate of taking three percentage points of your Social Security contribution and putting that into a private account, which you could then pass on to your heir. We did a lot of work on that. He was very enthusiastic about it, went around the country talking about it. And there was a surplus, a budget surplus in 2000. And his idea was that he would use this budget surplus for the transition to this new form of Social Security. But then 9-11 hit. And I was in the office of the National Economic Council Director, Larry Lindley. At the time, the plane hit the World Trade Center. The first plane hit, and someone came out of the meeting, came into our meeting, said, a plane hit the World Trade Center. We were discussing whether it was a transportation issue, who should take charge of it. Then we left the meeting at 9-15. The second plane hit, and then we knew it was not an economic issue. It was a defense issue. And we went back to our office in Inverness. The director of the National Economic Council was hustled away to a basement room, and the rest of us were told just to run, get out of the building, go north, because they thought that the plane that went down in Pennsylvania was aiming for the White House, and they wanted us to get out of there. I moved to get my car out of the parking lot between the White House and the old executive office building. The Secret Service said, no, there's no time for that. Just go, just run north. They obviously thought something was imminent. And I always thought, I still remember how brave they were, just standing there saying, something's going to happen. We're staying here, but you need to get out of here. And that was also a big memory of my time there being actually in the White House on 9-11.”

Jon: “Interesting.”

Diana: “Then after that, of course, we couldn't talk about, well, the money for the surplus went to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It went to fight terrorism. It went to fight the war on terror. So, then we could not go forward with the privatization of Social Security, or I shouldn't even call it privatization, because that's what gets privatization a bad name. It was allowing three percentage points of your contribution to go to a private fund. And if you imagine what that would have been like in 2001, the stock market has grown so much since then. If we'd allowed everybody to do that, people would have been so much better off now, Social Security would have been in a much, much better position. There are major inequities in Social Security where low-income Americans die earlier, minorities die earlier. So, they lose out from Social Security. They don't get the stream of funds that they would have if they lived to their 90s. So, this would have enabled them to have a pot of money that they could have passed on to their heirs, because they would have owned those three percentage points. So, this was really a very foresightful idea by President Bush, and it's really too bad that it was not implemented.”

Jon: “Fascinating. And so, you also served in the Labor Department under Secretary Chao. I'm curious, what were your main priorities there? I know there was one push to bring more transparency to union expenditures. Can you explain a little bit more about that?”

Diana: “Yes, a very important initiative of Secretary Elaine Chao was to make it clear to union members how their funds were being spent. Because before she took over, unions could just put down on their accounts $1 million, expenses, $500,000, other. They could literally say other. They wouldn't have to reveal how they spent it. But these dues going to the unions, they came out of union members' paychecks. And Secretary Chao thought it was very important that there be transparency, that these union members would know exactly how their dollars were being spent. So, she put in place what was called the LN2 rule that required unions to specify if all expenditures were over around $200, to itemize and say what they were. And as a result of this, some of the expenditures were no longer so common. So, if there were expensive hotels or golf trips or expenditures on T-shirts, union bosses would have to reveal that. Otherwise, members would complain. I think this was one of the most important things that Secretary Chao did when she was Labor Secretary, is that transparency, so that all these hardworking union members could see what was going on with their dues.”

Jon: “Fascinating. An interesting time, to say the least, for Labor policy and economic policy as well, in that early 2000s, pre-Great Recession era. I want to fast forward to the Trump administration, and I want to talk a bit about your time at the Transportation Department. You served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology. I'm curious, like, what does that involve, that particular role?”

Diana: “So the Office of Research and Technology has a vast empire within the Transportation Department. There's the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. There's the entire Volpe National Transportation Systems Research Group in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that has 1,000 people and does path-breaking research. There's the Transportation Safety Institute in Oklahoma City, which has an entire plane graveyard, a graveyard of broken bits of plane that come down, so that inspectors can learn why a particular crash happened. Plus, my group had a billion dollars' worth of research funds in the different modes. That's the Federal Aviation Administration, the Transit Administration, the Highway Administration to oversee. So, there was a lot to do. But most of my time was spent on this tiny little office, the Office of Positioning Management and Timing and Spectrum Management, which dealt with GPS and dealt with spectrum. Spectrum are these airwaves that most people don't even know exist. They make a phone call. They don't know it because their telephone company has bought a group of these airwaves, which are known as spectrum. And the Transportation Department was allocated spectrum for automotive safety. It was allocated 75 megahertz for the 5.9 band, a band of spectrum, and the Federal Communications Commission wanted to take it away for unlicensed Wi-Fi. That's the kind of Wi-Fi that you get if you sit down in the airport in San Francisco and you get on your phone and it says free Wi-Fi, click here, or Dallas airport, free Wi-Fi, click here. And there's really no reason the Wi-Fi should be free, but there are a lot of big companies that wanted free Wi-Fi. Why? So, you could surf the Internet, so you could go shopping, so you could get ads. And they came and lobbied the Federal Communications Commission every day, saying we need more free Wi-Fi, more free Wi-Fi, so they wanted to take away our spectrum. That would have been used for connected vehicles, so cars would have access to spectrum and then when it looked like they were going to bang into each other, there would be some kind of warning. Or a car could be connected with a pedestrian via cell phone, so if a pedestrian was going to step off in the car and there might be an accident, then the car and the pedestrian would have a warning. And these things could be on traffic lights, so if two cars were going towards each other and they didn't know they were going to be hitting each other, again, it could give that kind of warning. And this technology had been building and developing for 20 years when the Federal Communications Commission first assigned these outweighs for the surface. And then the Federal Communications Commission just said they were going to take it away. So, there was a big battle. The FCC ended up taking more than half of it away. There's some left. I don't know if it's enough for all the automated vehicles, the intelligent transportation systems that want to run it, the buses that would be able to change the lights to green from red if they were behind schedule, the ambulances that if they were rushing to an accident, again, could change all the red lights to green lights so that they wouldn't be going across, breaking a red light going across an intersection. So, we thought it was very short-sighted of the Federal Communications Commission. This was one of the many battles we were involved in, another involving a company putting itself right next to the global positioning system band, and then a third one involving radar alternatives on airplanes, these little devices that tell an airplane how far above ground it is. And again, there was an auction of airwaves that put in danger some of the radar alternatives. And the Federal Aviation Administration had to threaten to close down some airports in poor visibility if these telecom companies didn't fall back on the big task they're going to put for 5G next to airplanes. So, it was a very exciting time, a very exciting time. And some of the most important research, the most important research, the most important research project I think I did was a grant to the National Bureau of Economic Research to set up a transportation economics program. And normally, when people talk about allocating high-speed rail, they don't say, well, how much is Diana going to pay for a high-speed rail ticket between San Francisco and Los Angeles? The way they say, how much would Diana be willing to pay for an iPhone 14? They just say, we're going to have high-speed rail because China has a high-speed rail. They don't do an economic analysis of it. But economics should be as much a part of transportation as it is of any other field. And so, the transportation department gave a grant to the National Bureau of Economic Research to set up a transportation program. And in April, I was at the first post-pandemic in-person conference at NBER. And there were transportation economists discussing subjects such as whether bus companies, a bus route does better in the presence of rail, or how are minibuses in Cape Town, South Africa doing? And it was just fascinating. I think that that's one of the most important legacies of my time at the transportation department. And the current administration has continued the grants to NBER for this project. And it's great that there are so many exciting young minds focused on how to make transportation more economical and how to align it more with economic principles, because it's a subject that really deserves more research.”

Jon: “It's fascinating to think about all the R&D and infrastructure in that domain. And certainly, rail's been a big topic. And it's, I think, a bit different to the U.S. in the sense that the U.S. is just a massive land mass. And it's somewhat more difficult to build sufficiently. And obviously, unions play a role in that, too. And how expensive it is to build some small amount of subway track in New York City is just enormously expensive. But meanwhile, you look at Florida, for example, and they built the right line, which is essentially a private sector project. And they built it from Miami to Fort Lauderdale. And they built it to West Palm now. And they're expanding it to Orlando. It's interesting how successful that's been, whereas I feel like other infrastructure projects like updating the New York City subway, or trying to get high-speed rail between, or some sort of rail between California between Los Angeles and San Francisco is so difficult.”

Diana: “Right, well, BrightLight is a private company. They estimated the demand. They looked at how much Jon or Diana would be willing to pay for a ticket from Orlando to West Palm Beach or Miami, or, and it's going to be extended to Tampa, too, I believe. And they saw that there are these tourists who fly into Orlando, and they also want to go to the coast. Or they're in Tampa, and they want to go to Orlando. Or they're in Miami, they want to go to Orlando. And they estimated the demand, and they put up this private high-speed rail. So, they really went through all the economic mechanisms to see that it would be worthwhile. Another interesting economic area is road paving. You might think road paving isn't interesting, or it's not an economic area, but really it is. And when I was going to the transportation department, my former chairman of the economics department at Swarthmore College said, Diana, you've got to figure out why there are potholes in the road. Why do we still have potholes? So, of course, I tried to figure out why there were still potholes. And one answer is, we were doing research into all these paving materials. We don't have to have potholes. But, of course, the non-pothole materials are much more expensive than the others. And states and cities and municipalities are limited in the amount of funds that they have. So even though it might be more affordable over 10 years to have better paving materials and have more money up front, they don't have more money up front. They just have a certain amount of money up front, and they can't afford the more expensive paving materials. So, it really makes you look twice at how these things are structured, and maybe there should be a better way of allocating more funds to begin with, thereby lowering the overall cost and reducing the number of potholes. And a lot of municipalities have not managed to do that.”

Jon: “Wow. It is fascinating. Yeah. All these infrastructure issues are so interesting.”

Diana: “And then, of course, the pandemic hit when I was the DFT. So, we had the Economic Rebuilding Task Force. We were asked to do so much more data collection because all the transportation networks were about to close down because no one was riding them. And then the federal government was subsidizing them to stay open. And we had to generate data on a daily basis showing what travel was as a percentage of pre-pandemic travel for all different modes. And we didn't have that right away. We had to get new data sources to do that because that's what the leadership of the transportation department wanted. And we had an Economic Rebuilding Task Force to deal with different problems that were arising in all the different modes of transportation during the pandemic. So, the last year was very much dominated by pandemic transportation. Fascinating. And you were also nominated for assistant secretary role at transportation each year, but your nomination was stalled for certain procedural reasons. Can you walk through, our listeners, what that process of Senate confirmation is like and what was going on at the time in terms of Senate confirmations and then Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and how he was prioritizing for reshaping the judiciary? Could you explain a little bit what going through that whole process is like?”

Diana: “Yes, yes. Well, in March 2017, shortly after the election, Secretary Elaine Chao asked if I would be the nominee for Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology because I had been her chief economist over at the Labor Department. And I was nominated in September 2017. I had a hearing in October. And the next step after you're out of committee, after the committee has voted you out, is to get a vote on the floor. But Senator Schumer was holding up candidates, not just me. Everybody requires 30 hours of floor time for a vote. Those were the Senate rules. So, it was very difficult to get that vote on the floor and thereby get position. So, to begin with, I was sent to the Treasury Department as Acting Assistant Secretary for Economic Policy because the Office of Personnel Management said, if you go to transportation before you've been confirmed, this is not going to make the Senate happy. They're not ever going to vote to confirm you. So why don't you go to the Treasury Department? Because that nominee for Assistant Secretary of Economic Policy, Mike Falken, is in the same situation you are. He hasn't been able to get his vote on the floor either. So, I went to the Treasury Department for about just under a year and worked on economic forecasts, went to the OECD in Paris to explain how U.S. growth was influenced by our lower tax rates, which, of course, they didn't want to hear. Meanwhile, I was waiting for this vote on the floor, and I had to be re-nominated every year. Well, in February 2019, I think presidential personnel got tired of this. They said, Diana, we need you over at DOT. Just go as Deputy Assistant Secretary, and we'll still try and get you confirmed as Assistant Secretary. And so I went, and I oversaw the research. I was waiting for the vote on the floor, but it didn't happen. And I was actually the longest-waiting Trump nominee not to get confirmed. But I was in the situation with many, many other people. There were many other positions for which the nominee was not confirmed just because of the polarization on Capitol Hill and the difficulties. The climate is so divisive that it's difficult to get people through. Senator McConnell quite rightly focused on judges because they have lifetime appointments, whereas Assistant Secretaries just come and go. And so, as a result, there are many, many talented judges who have their jobs. And I still believe that I contributed a great deal to the transportation plan with the Deputy Assistant Secretary title rather than the Assistant Secretary title.”

Jon: “That's fascinating. I'm curious, like, what are these OECD meetings in Paris like? It's an interesting organization, and we hear about it a fair amount. They put out a lot of great data that economists like to use that typically, like, normalizes it across countries. But it also is sort of like a meeting or a gathering place. We actually have an ambassador to the OECD. I know, like, I think three of their key sort of deputy positions at the OECD are typically controlled, like, by three different, I think, regions or countries. There's, like, one representing the U.S., one from Europe, and one from Japan. What are those meetings like when you go to Paris? What was it like at the time?”

Diana: “They're very formal. People are assigned seats, and they're very, very descriptive. So, people knew what I was going to say in advance, and I had a time slot. I was actually with a Hoover Institution fellow, Tyler Goodspeed, because he was assigned from the Council of Economic Advisers also to go to these same meetings.”

Jon: “Right. He was acting chair at the time.”

Diana: “Well, even before he was acting chair, he was the member who went.”

Jon: “Oh, okay, got it, got it.”

Diana: “Yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah, so he went as a member, and then I went as acting secretary of economic policy. So, there's a Treasury representative and a CEA representative. So, we went together. And, yeah, we made speeches. We met with the different people there. It's a very, very formal atmosphere. We get a chance to meet people more informally during the coffee breaks. It's a very interesting organization.”

Jon: “Fascinating. And then the assistant secretary for economic policy role is an interesting one at Treasury. Typically, that involves, I think, briefing the secretary on things like jobs reports and walking through economic data releases. What does that role involve? And I'm sure it changes from administration to administration as well. But from your experience, what does that role involve?”

Diana: “Well, the most interesting part is you get to see the economic data the night before. So, I would see the economic data the night before, and I would get to explain it to Secretary Mnuchin.”

Jon: “Right. So, you're like one of the, like, four or five people in Washington that get these economic data releases, like non-farm payrolls.

Diana: [Overlap 37:57] the economic advisors at the Treasury secretary, the president gets it, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, just a few people who get it. Anyway, so it's really exciting to get it. And then when he was away, when he was out of town, then I would have to go to a secure room and give a memo that would get to him through some encrypted way. I couldn't just call him up and say, Secretary Mnuchin, here are the data. So anyway, the most fun part of the job is getting the data the night before. And then when there's – so some Treasury secretaries, you would brief them as to what to say at press conferences. But Secretary Mnuchin never needed any of that. I mean, he was very familiar with all of the economic issues, and he didn't need a lot of briefing.”

Jon: Right. Former Goldman Sachs partner and a longtime Wall Street financier veteran. Fascinating. So, I want to fast forward now to the work that you're doing at the Heritage Foundation. You're doing a lot of very interesting work on environmental regulatory policy and transportation regulatory policy. We've had some interesting discussions on self-driving cars and what that's like. I'm curious, what are the big things that are interesting to you right now?”

Diana: “What's interesting to me is how the government is trying to reshape the economy through regulation. So last year, about 6% of new vehicle sales were electric vehicles. And the Environmental Protection Agency is putting forward a proposed tailpipe emissions law, which would result in 60% of vehicle sales being battery-powered electric by 2030, and about two-thirds being battery-powered electric by 2032. This is just a dramatic change in the way Americans drive. Because first of all, they would have to recharge these vehicles rather than going to the gas station. And not all Americans have charging stations in their homes. And these vehicles are much more expensive. So, the best-selling car in America is the Ford F-150 pickup truck. And the electric version is about $10,000 or $12,000 more than the big internal combustion engine version. And plus, the Ford Lightning, the electric version of the F-150 doesn't tow anything, because it would need a lot more strength for the battery to actually be able to do tow. So, it's quite a different vehicle. And the vehicles don't work very well in cold weather. So that's why Wyoming just has 510 battery-powered electric vehicles. Because all of us have woken up and found that our battery in our regular car is dead because of the cold. I mean, if you're driving an electric vehicle, it loses 20 to 40% of its charge in cold weather. So that's a major disadvantage. So, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Alaska, there are very few electric vehicles. So, this would really reshape the way Americans drive. And it would just take away the freedom just to get in your car and drive wherever you want. You could drive wherever you wanted as long as they had a charging station, and not too many people were waiting to charge up their vehicles at the charging station. So, I've been doing a lot of work on that, on the disadvantages, and trying to explain the myth of net zero 2050. I have a talk I give on campuses called Santa Claus, the tooth fairy, and net zero 2050. And I ask, how many believe in Santa Claus? How many believe in the tooth fairy? And how many believe in net zero 2050? Because we've even had executives from oil companies come and visit us at Heritage and talk about their transition to net zero. And I asked one of them, I said, Ed, do you really believe that we're going to net zero in 2050? He said, well, within these four walls, I can tell you that I don't. But outside, I can't say that because people would call for divestment of our stock. So, this thing, I mean, it's not going to happen, net zero 2050. Even if we could paper over all of America with solar panels and have wind turbines everywhere, and even if we could generate all of America's electricity from solar panels, hydropower, and wind turbines, you still need fossil fuels to make the wind turbines. You need fossil fuels to make the solar panels. You need fossil fuels to have a backup for the wind turbine, when the windows blow, it’s myth, it’s never going to happen. The people talk about it, it’s part of this environment, social, and governance movement.”

Jon: “Fascinating.”

Diana: “Yeah.”

Jon: “There's been a lot of talk recently over the Inflation Reduction Act passed last year and it certainly, I think introduced a lot of spending in the area of electric vehicles. Could you explain a little bit about what the so-called Inflation Reduction Act is doing in that space?

Diana: “It would give substantial grants for different types of green energy and it would also give grants for certain cars if supposedly, if they're made in the United States with American components, they would get a $7,500 credit to buy that EV. But the Treasury just decided that commercial vehicles are all allowed to have the tax credit. And if you lease a vehicle, that counts as a commercial vehicle. So anyone can lease an EV and get the tax credit, which is really going around what Congress wanted. Congress also gave tax credits for battery plants in the United States to try to bring the battery manufacturing back from China. Right now, 80% of the world's batteries are produced in China. One big concern that people have with electric vehicles is it would make us more dependent on China. Right now, we're independent in terms of oil and natural gas. We are a net oil and natural gas export. But if we can't rely on these fuels to power transportation systems, then we would be dependent on China for the batteries. Because the cost differentials are just too great to have all the batteries made in the United States. China subsidizes the capital because they give artificially low interest rates to favored companies. The labor is lower, not just because wages are lower, but because China uses forced labor from Xinjiang Slave laborers, the Uyghur population is put in concentration camps. And energy, China is still building more coal-fired power plants, and its carbon emissions are increasing every year. It has pledged that it will reduce carbon emissions by 2027, but it's not doing so yet. So basically, on labor capital and energy, they have an advantage over us. We're never going to be able to produce batteries at the same cost that they come from China. So, we're giving political power, we're giving our power dependence, our energy dependence to China with these electric vehicles. The components also are manufactured in China So, it's a very big problem that people should be more focused on. And as that’s by parties are concern about China parts. It's not Republicans or Democrats, everyone's concerned about Chinese aggression, Chinese power. So, this is a very serious subject to be looking at.”

Jon: “Fascinating and I want to talk about self-driving cars. So, I remember seven or eight years ago when I was in business school in 2015, one of the biggest things then was self-driving cars. And there was this sort of prediction that in 10 years we would all have self-driving cars. What exactly is going on in the self-driving space? I'm curious, around San Francisco you'll sometimes see these self-driving cars go around, largely still have human drivers in them. But I'm curious, where do you think this has the potential to disrupt things like trucking? And how soon do you think that that is going to take place?”

Diana: “The first thing we have to be able to do before having self-driving cars is have a car that stops before it hits something. If we can just get our current vehicles or new internal combustion engine, new vehicles with drivers, to be able to stop before they hit something, we will have a real achievement and we will really reduce the number of people killed on the roads. 40,000 plus people killed on the roads every year. So, until you can get a vehicle, until you have the technology to get a vehicle to brake before it hits something, we're never going to have self-driving cars because that's criteria number one and we can't do that. But self-driving trucks, I think those are another story. There's a company called Locomation which has what's called convoying trucks. And truck number two is behind truck number one. And it has sensors that keep it the right distance apart. And the driver in truck number two can go to sleep on the highway while driver number one drives. And this is important in trucking because there are new isles of service rules. You can't drive more than 11 hours at a time. That means that for 13 hours, your truck, this immense expensive piece of capital, is basically still and not usable. So, if you can just have a truck number two follow truck number one, and then when truck number one has, the driver has exhausted his isles of service, he goes to sleep, truck number two pulls ahead and they continue down the road. That's an immense achievement. So, I can see a big potential for these convoying trucks. They follow a certain distance behind. And the way they're set up right now, when the trucks are in the city, both drivers are awake. Once they're on the highway, driver number two can go to sleep and then they switch positions. So, I think that driverless trucks are going to come before driverless automobiles, unless the automobile is on a fixed route. When you go to an airport now, you generally get on a driverless train that takes you in between terminals. You can see that driverless trucks can take you on a fixed route between terminals, or maybe between a senior citizen's home and a hospital, something like that. But to have them fully around everyone, we're not going to get that until we can get these cars to brake before they hit something. And they have to be able to distinguish, by the way, between a child running in front of the car and a paper bag or a plastic bag blowing in the wind in front of the car. It's not a simple matter.”

Jon: “Wow. It's fascinating just to think the degree to which it could really disrupt such a big industry like trucking and all the important regulatory considerations that go in hand with that. I also want to talk just on this whole conversation of energy. I want to talk a little bit about nuclear energy and why is it the case that nuclear energy has basically been at a standstill in the U.S. for many, many decades and why new nuclear power plants can't be built. And I think there's a number of reasons why this is the case, but I'm curious to hear your thoughts.”

Diana: “There are a lot of regulatory obstacles to nuclear power, and I'm not an expert in this, but it certainly produces dense emissions-free energy. And I have a colleague, Jack Spence, who's writing a book on it, who's looking at the different obstacles to nuclear power. And we're not at Heritage at all suggesting any subsidies or any government funding for nuclear power, but we need to have a serious look at these regulatory obstacles and encourage more nuclear power plants to be built. There's one being built in Georgia right now that's about to go online with Southern Company. There's also the small modular reactor that can be brought into certain areas, provide energy, and then be taken out once their fuel is spent. These may be very good for emerging economies in Africa, Latin America, that need more dense energy. Because as you might know, Jon, the World Bank is prohibited from lending money for nuclear or for coal-fired power plants, and these countries cannot get to the level of the West unless they have some dense energy sources. They need to have electricity, they need to have running water, they need to have sanitation systems, they need to have electricity so they can have manufacturing plants. And one of the reasons that we see the vast migrations that we do, people from Latin America trying to come to the United States, people from Africa trying to come to Europe, is because of the differential levels of energy. The West has benefited tremendously from fossil fuel energy. We can recharge our cell phones at night. We don't generally have blackouts unless we're in California. We can drive where we want. We have running water. We have sewage systems. And other countries need to get that same kind of energy so they can come up to our living standards. And it's immoral for us to say that we have reached this place, but we're only going to allow emerging economies to generate electricity through hydropower, wind, and solar from now on because that damages the environment.”

Jon: “Well, I want to talk a little bit about natural gas for a second because you know, nuclear energy has been sort of stalled and it's declined, I think, quite unfortunately in largely all parts of the world. In Europe, it's been a huge issue. Certainly, it's the Russian invasion of Ukraine where countries like Germany and France could be in a much better place if they had better nuclear infrastructure and that they weren't closing down nuclear plants. They wouldn't be so reliant on Russian gas. Similarly, I think what's interesting about the whole natural gas story is there's a lot of regulatory barriers to it. But in the U.S., you know, it's been enormously an increasing source of energy and it is less carbon intensive than things like coal. I'm curious, like, what do you think the barriers are to natural gas and its further expansion?”

Diana: “We have vast amounts of natural gas here in the United States and the barriers to expansion are, first of all, there's barriers to leasing on certain federal lands, offshore development, and also pipelines. We have a number of different agencies that are slowing down pipeline approval. There's the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission that has to approve these pipelines. There's the Interior Department. There's the Securities and Exchange Commission, which is looking at climate risk of companies' projects. There's the Office of the Control of the Currency, which is a climate risk office that's looking at banks’ lending for climate-related projects. Guess what? Pipelines count as climate-related projects. So do developments in terms of natural gas claims. So, there's big pressure from different parts of the federal government not to produce the gas, and even if we have it, not to have the terminals in the pipelines that allow it to go out to consumers or to terminals where it can be exported abroad to offset the cuts from Russia. So, this is in the United States. The United States is particularly advantageous in terms of the property rights situation, where if someone discovers natural gas under their land, they're allowed to get permission for fracking. This isn't true in other countries. In many other countries, such as Britain, my home country, everything under the ground belongs to the crown, King Charles, in fact, or the government. So, if you find natural gas on your property, you don't have permission to use it. You don't have a financial incentive. It's not yours. And it's like that in many other parts of the world. People don't own what's under their property. And that's why natural gas, even though it could be fracked in other countries, the financial incentives are not there often, plus there's environmental concerns. But emissions in the United States have gone down by about 1,000 million metric tons over the past 15 years. In China, they've gone up by about 5,000 million metric tons. Our use of natural gas is really driving the carbon emission.”

Jon: “Absolutely. I mean, to me, it seems quite crazy that you would want to halt the construction of LNG pipelines, LNG terminals, that would allow the export of further natural gas around the world. It seems to me like it's a hugely carbon-reducing agent, the introduction of natural gas and horizontal drilling and fracking over the past decade or the popularization over the past decade or so. And it seems wild to me why someone would want to halt something that on net would be a hugely carbon-reducing activity, that is further exporting of natural gas and further reliance on it.”

Diana: “You can just look at New York State, Jon, which has the Marcellus Shale. So, the Marcellus Shale is equally in New York State and Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania has developed its share of the Marcellus Shale, but New York hasn't. So, there's a lot lower income in parts of rural New York State compared with rural Pennsylvania. New York State won't let the pipelines through, so that means you can't get natural gas up to New England, and it has to be heated by oil, frequent oil. There's a lot of oil heating in homes, and until the war with Russia, Russian tankers could be found refueling oil in New England ports. So, there's real need for more energy in New England, and yet you can't even get a pipeline through New York State.”

Jon: “Wow. Fascinating. Well, Diana, this has been an amazing conversation, just hearing about your experience in government across four different presidential administrations, hearing about some of the most consequential economic policy decisions over the past two decades, and hearing about your very interesting and fascinating thoughts on where we're going with environmental regulatory policy, infrastructure, and research and development in areas of things like electric vehicles, self-driving cars. It's been a really fantastic conversation, and I really want to thank you for joining us. It’s been reallt fantastic.”

Diana: “Well, thank you so much, Jon. Thanks so much. It's really been great talking to you today. Thank you.”

Jon: “Today, our guest was Diana Furchtgott-Roth, who's the director of the Center for Energy, Climate, and Environment at the Heritage Foundation. This is the Capitalism and Freedom, the 21st Century Podcast, where we talk about economics, markets, and public policy. I'm Jon Hartley, your host. Thanks so much for joining us.”